How to get FDA approval : Pick the Right Pathway

If you are building a medical product, “FDA approval” is not a single finish line.

The first real job is to pick the right FDA pathway early, based on what your product is and what it claims.

This guide is written to help startup founders avoid the most expensive mistake: building for the wrong pathway.

FDA approval is not one thing (and not for every product)

Who this guide is for ?

If you are a founder or early product lead, this is for you.

Especially if you have not contacted the FDA yet and you are still shaping claims, workflows, and evidence.

I have seen teams rush into an FDA meeting hoping the agency will “tell them what they are.”

That usually backfires. A first FDA interaction goes best when you bring a pathway hypothesis, a tight intended use, and decision-ready questions.

This guide is a master map. The goal is to help you pick a pathway on purpose and show up prepared.

What the FDA actually checks ?

The FDA’s core concerns are surprisingly consistent. They want to know your product is safe, works as claimed, and can be made reliably.

Across drugs and devices, the FDA looks at:

- Safety: What harms could occur, and how you reduce risk

- Effectiveness / performance: Does it do what you claim, in the intended population and setting

- Labeling: The exact claims, indications, contraindications, warnings, and instructions

- Manufacturing quality: Whether you can consistently produce what you tested and validated

Founders often treat labeling like marketing copy. FDA treats labeling like a risk control. If you over-claim, you raise your evidence burden and your risk classification.

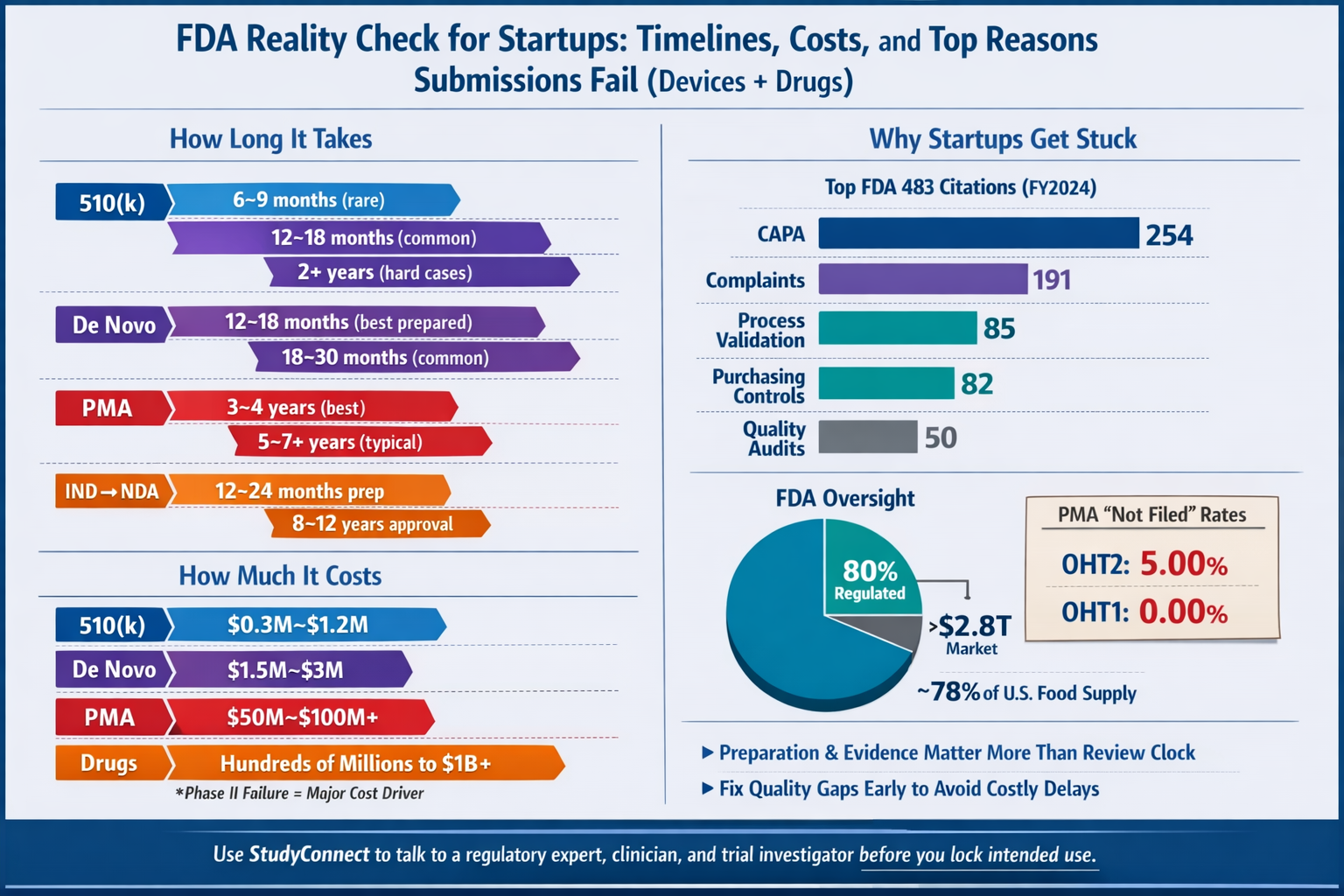

Manufacturing and quality also matter earlier than most startups expect. For device companies, FDA inspections frequently cite basic quality system gaps like CAPA and complaint handling (see data later in this guide).

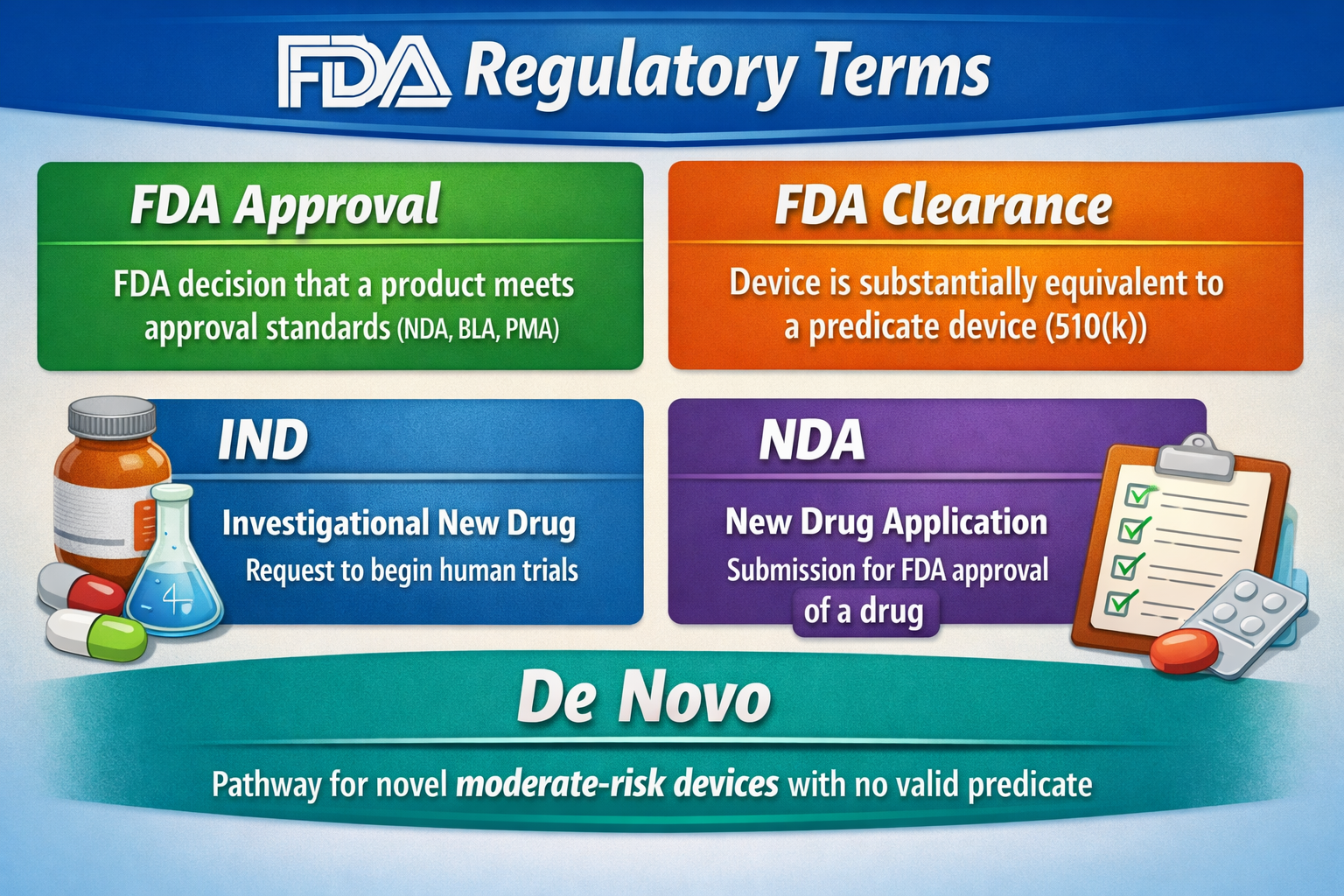

Approved vs cleared vs authorized vs registered/listed ?

These words are not interchangeable. Using the wrong one in investor decks can create confusion fast.

- Approved: Common for drugs (NDA) and high-risk devices (PMA)

- Cleared: Common for many medical devices via 510(k) (substantial equivalence)

- Authorized: Commonly used for Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) situations

- Registered/listed: Many companies must register their establishment and list devices, but that is not “approval”

Common myths that get startups blindsided

Myth: “FDA approves everything”

The FDA regulates a lot, but not everything. And even within FDA scope, not everything is “approved.”

A useful reality check: FDA says the products it regulates account for ~20 cents of every U.S. consumer dollar and it oversees >$2.8 trillion in annual consumption

(FDA “FDA at a Glance,” Nov 2020). That implies ~80% of consumer spending is outside FDA product jurisdiction (housing, transport, many consumer goods, and more).

Even within “health-related” categories, boundaries matter:

- The FDA oversees ~78–80% of the U.S. food supply (GAO report Jan 8, 2025; FDA Human Foods Program page)

- But most meat/poultry/processed egg products are regulated by USDA FSIS, not FDA (CRS report, ~2025)

- Alcohol labeling and advertising is regulated by TTB, not FDA (TTB page, ~2025)

Why this matters: your product category determines your regulator, your submission type, your evidence, and your timeline.

Myth: “We will ask the FDA what pathway we are”

The FDA is not your product strategist. They will not brainstorm your category from scratch.

In practice, the FDA expects you to propose:

- A specific product type and intended use

- A pathway hypothesis (510(k) vs De Novo vs PMA, or IND→NDA/BLA)

- The key risks and mitigations

- Specific questions tied to decisions you need to make

If you show up with “What are we?” the FDA will usually respond cautiously.

And they may default to the highest-risk interpretation if your claims are vague.

Myth: “Phase 1 means it works”

Phase 1 does not prove effectiveness. It is mainly about safety, dosing, and how the drug behaves in the body.

Typical clinical phase success rates shared in the expert breakdown are:

- Phase 1: ~70% pass

- Phase 2: ~33% pass

- Phase 3: ~25–30% pass

This is why “positive Phase 1” is not a launch moment. It is the start of the hard part: proving it works in the intended patients.

Which FDA pathway applies to your product?

Start with Product Type -

Drug/Device/Biologic/Cosmetic

Your “type” is not what you call it. It is what the product does and what you claim it does.

A simple decision tree works well:

- Does it achieve its main intended purpose through chemical action in the body? - Often a drug (CDER) or biologic (CBER)

- Is it an instrument, software, implant, or tool that diagnoses, treats, or affects patient care without chemical action? - Often a medical device (CDRH)

- Is it food, dietary supplement, cosmetic, or consumer wellness? - Often CFSAN (with boundary checks like USDA for meat)

Then ask the most important question:

What is your intended use statement ?

If your intended use implies diagnosis, triage, or time-critical clinical action, you are likely in device territory even if you call it “analytics” or “workflow software.”

Before you talk to the FDA: the deliverables most startups forget to do

Most slow or unproductive FDA conversations fail for one simple reason: the company shows up without having done the definition work. When that happens, the FDA doesn’t “help you figure it out.” They push the discussion back to basics—what the product does, what it claims, who it’s for, and how it fits into real clinical workflow. That reset costs time, money, and momentum, and it’s almost always avoidable.You don’t need a massive regulatory package before your first FDA interaction. You do need a small set of clear, defensible deliverables that show you understand your product at a regulatory level. Teams that bring these move forward. Teams that don’t tend to stall.

Intended use is a technical definition, not marketing copy

Your intended use statement drives everything: risk classification, pathway choice, evidence expectations, labeling, and post-market obligations. If it’s vague or aspirational, everything downstream becomes harder.A strong intended use statement clearly defines who the user is, what data the product analyzes, what output it produces, and the specific clinical purpose it supports. Just as important, it explicitly states what the product does not do. Those exclusions are not legal filler; they are how you control risk and evidence burden.The most common mistake founders make is pasting marketing language into regulatory documents. Marketing expands scope. Intended use must narrow it. When scope creeps, risk rises, and the FDA responds accordingly.

Have a pathway hypothesis before you ever talk to the FDA

If you go to the FDA asking, “What are we?” you are not ready for that meeting. You should arrive with a clear hypothesis about your regulatory pathway and a concise explanation for why it fits. This does not require a long memo—two or three pages is enough if the thinking is solid.A good pathway hypothesis briefly describes the product and intended use, states the proposed pathway, and explains why that pathway makes sense given the product’s risk, novelty, and precedent. For devices, this includes an honest predicate assessment if a 510(k) is claimed. Intended use alignment matters far more than technical similarity, and this is where many teams misjudge their position.

If you cannot find a clean predicate, that is not a failure. It is a signal. Forcing a 510(k) anyway is how teams lose a year.

Risk comes before accuracy, and workflow comes before metrics

The FDA does not start with model performance. They start with harm. Specifically, they want to understand what happens when your output is wrong, delayed, or missing.Before engaging the FDA, you should be able to explain where your product sits in real clinical workflow, what decisions change because of it, whether it triggers escalation or prioritization, and what users do if the system is unavailable. This context is what gives meaning to any accuracy or performance claim.A preliminary hazard analysis should address incorrect outputs, downtime, bias across populations, data drift, misuse outside the intended population, and user over-reliance. Each hazard should be paired with concrete mitigations such as labeling limits, UI design, human-in-the-loop controls, monitoring thresholds, and update rollback plans. Teams that lead with accuracy but can’t explain harm pathways usually get slowed down quickly.

Engineering discipline still matters, even if you’re “just software”

Software teams often underestimate how much engineering rigor the FDA expects. You don’t need a perfect quality system early, but you do need a real one. That means being able to explain your system architecture, model type and autonomy, human decision points, deployment model, update strategy, and version control approach.Data provenance is especially critical for AI systems. You should know where your training and validation data came from, how ground truth was defined, which populations were included or excluded, and what limitations exist. Regulatory documentation is inherently multidisciplinary, spanning medicine, engineering, and quality. Teams that treat it as a serious, shared responsibility move faster and avoid painful rework.

The takeaway is simple: the FDA is not looking for perfection in early conversations. They are looking for clarity and seriousness. If you show up with a tight intended use, a defensible pathway hypothesis, a risk-first mindset, and basic engineering discipline, the conversation changes completely.

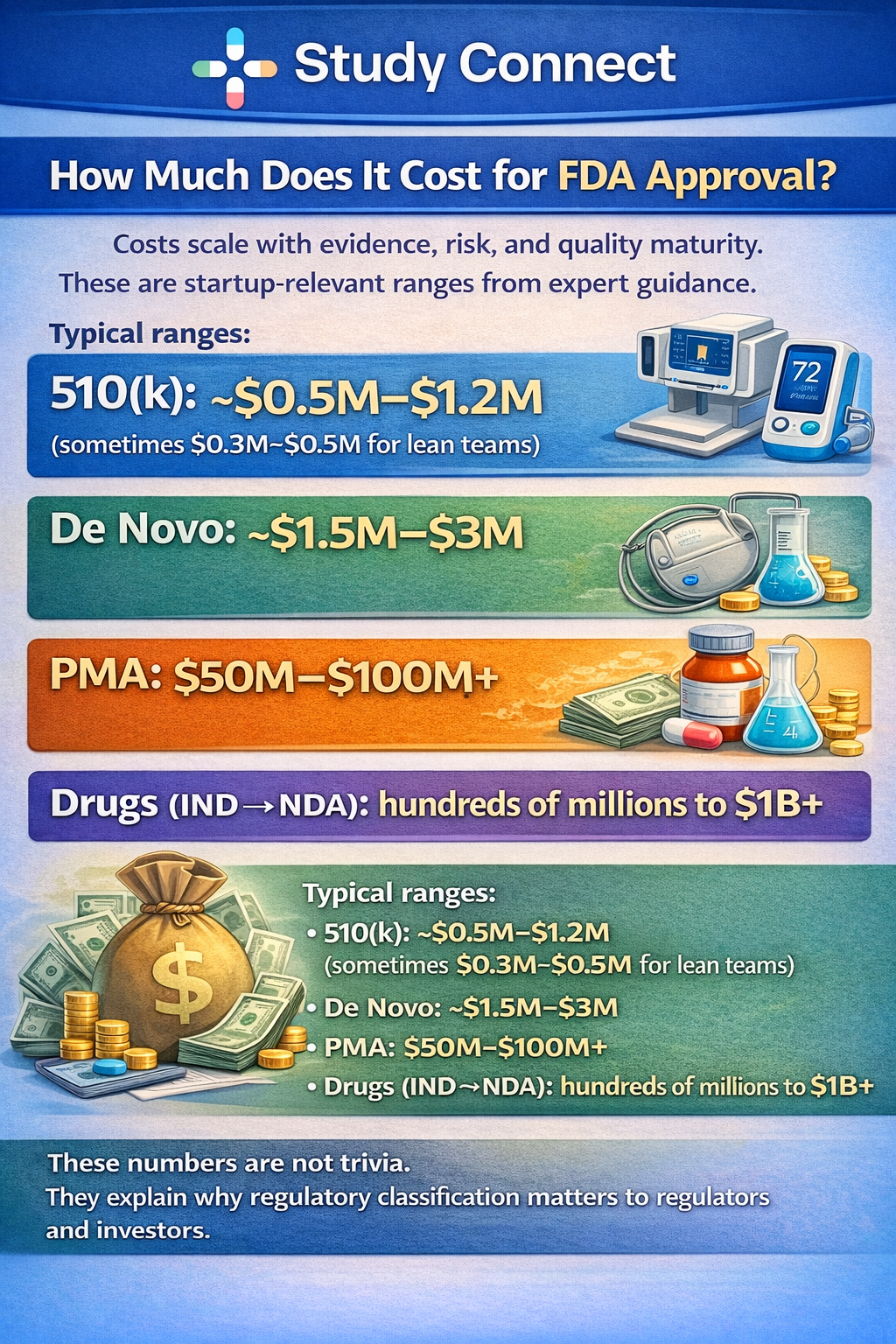

How much does it cost for FDA approval?

What drives spend:

- Prospective clinical trials (design, sites, monitoring)

- Data collection and labeling/ground truth work

- Quality system build-out and supplier controls

- Regulatory writing and response cycles

- Manufacturing scale-up and inspections (especially drugs and PMA devices)

What delays most often ?

Most delays are avoidable with early clarity. Here are the common ones across pathways:

- Intended use is vague, broad, or changes midstream

- Predicate device is weak or not truly equivalent (510(k) stalls)

- Risk analysis focuses on accuracy, not harm pathways

- Clinical endpoints are not tied to intended use claims

- Data provenance is unclear (especially AI/ML systems)

- Quality system gaps appear late (CAPA, complaints, supplier controls)

- Poor inspection readiness for manufacturing sites

- Resubmissions triggered by deficiency letters or CRLs

Practical tools and databases (so you can verify, not guess)

- FDA Product Classification - Use it to find how similar devices are categorized

- 510(k) Premarket Notification database - Use it to find predicates, indications, decision dates, and summaries

- FDA drug approval database and FDA Drug approval list

How can StudyConnect help you ?

StudyConnect is useful before you lock your pathway and evidence plan. It helps you talk with verified clinicians, researchers, and trial investigators to pressure-test:

- Intended use wording and exclusions

- Where the tool sits in real workflow

- What “harm” looks like if output is wrong

- Practical endpoints and trial feasibility

- Labeling boundaries that clinicians understandThis is not about replacing regulatory counsel.

It is about reducing guesswork early, so your regulatory plan matches clinical reality.

Get in touch with the team at StudyConnect at matthew@studyconnect.world to help you connect with the right medical advisor.

Quick Checklist

One-page checklist: what you need by stage (pre-sub, build, submit, post-market)

Pre-Sub stage

- Intended use statement (with explicit exclusions)

- Pathway hypothesis memo (2–3 pages)

- Predicate search record (if 510(k))

- Device description + architecture diagram

- Workflow impact map (before/after)

- Preliminary hazard analysis + mitigations

- Data provenance summary (AI: sources, labels, ground truth)

- 5–10 FDA questions tied to decisions

Build stage

- SDLC process and version control

- Design controls mindset (requirements → tests → traceability)

- Complaint handling process - CAPA approach

- Supplier controls (cloud, data vendors, critical components)

- Verification and validation protocols

- Labeling draft tied to evidence

Submit stage

- Final submission package (device/drug specific)

- Final validation reports

- Final labeling

- Risk management file (as applicable)

- Manufacturing documentation (as applicable)

Post-market

- Monitoring plan and complaint intake

- Reporting obligations

- Update control process (especially software/AI)

- Post-market studies if required

Have a query ? Reachout to us at support@studyconnect.org.