Clinical Trials for Startups: The Ultimate Guide (Avoid Costly Delays)

Clinical trials are rarely "just a study." For startups, they are a long, expensive coordination project with science attached. Most delays come from misunderstandings, not regulators. This guide helps you decide what to do now, what to delay, and what not to mess up.

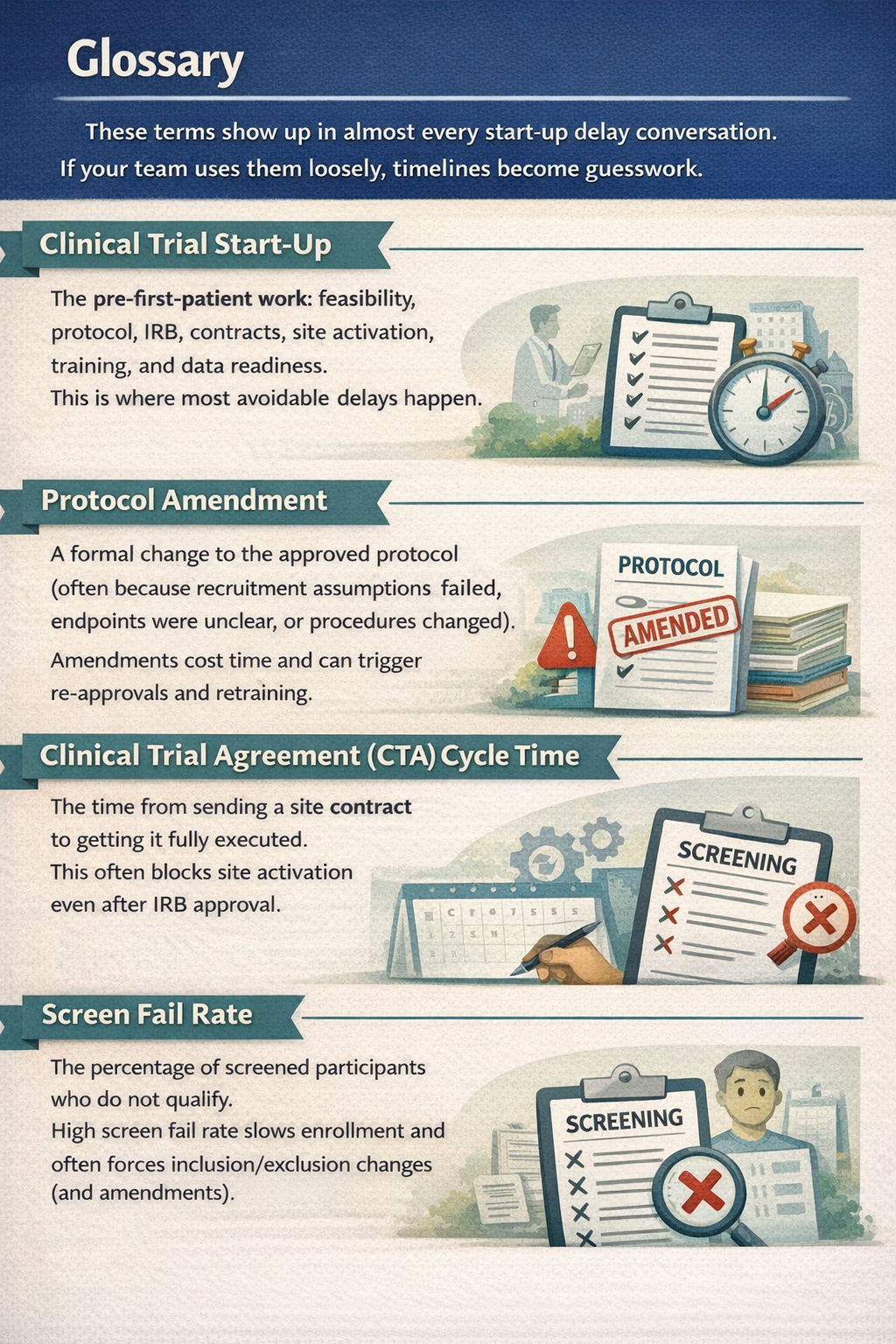

What is Clinical trial start-up and Why it matters ?

Clinical trial start-up is everything that happens before the first patient is enrolled. It includes feasibility checks, protocol writing, IRB submission, contracts, and site setup. If you are a founder, this is where timelines quietly double. Not because regulators are blocking you, but because your own decisions are still moving.

Here is what typically happens before "first patient in":

- Decide your claim and intended use (what you will say publicly and clinically)

- Choose study type (interventional vs observational, prospective vs retrospective)

- Draft protocol and consent language

- Pick IRB strategy (central IRB vs site IRB)

- Confirm whether FDA involvement is needed (IND/IDE or not)

- Contract with sites (Clinical Trial Agreement)

- Set up data systems, security, training, and documentation

I have watched teams lose 6-10 weeks just on "small protocol wording" debates. Those are not small. They change inclusion criteria, endpoint definitions, and data needs.

A helpful starting point is the FDA's official guidance library.Use it as a guardrail while drafting your protocol to reduce later amendments: See FDA Clinical Trials Guidance Documents

Clinical trial vs clinical study: What's the difference

A clinical study is any research involving people.

A clinical trial is a type of clinical study where you assign an intervention.

In practice:

Clinical study (broad):

· Observational (you observer outine care)

· Retrospective chart reviews

· Surveys and usability work(sometimes)

· Registry studies

Clinical trial (narrower):

· Interventional

· You assign a drug, device use,behavioral intervention, or workflow change

· Often has more safety oversightand monitoring requirements

Founders mix these up because both can involve patients, sites, and IRBs.

But the differences affect your timeline, approvals, and cost.

Interventional vs non-interventional

Interventional: You change what happens to a participant.

Example: you assign use of a device or an app that alters care decisions.

Non-interventional /observational: You collect data without changing care.

Example: you observe outcomes based on routine practice.

Clinically validated

This phrase is often used loosely. In a startup context , it should map to a claim.

- If your claim is "users like it" - usability and human factors evidence may be enough.

- If your claim is "improves workflow" - operational metrics + observational evidence may help.

- If your claim is "improves outcomes" - you are moving toward clinical endpoints and likely need stronger clinical evidence.

- If your claim is "diagnostic performance" (sensitivity/specificity) - you need validation aligned to intended use and population.

If your claim is regulated, you must design evidence for that claim. There are no shortcuts here.

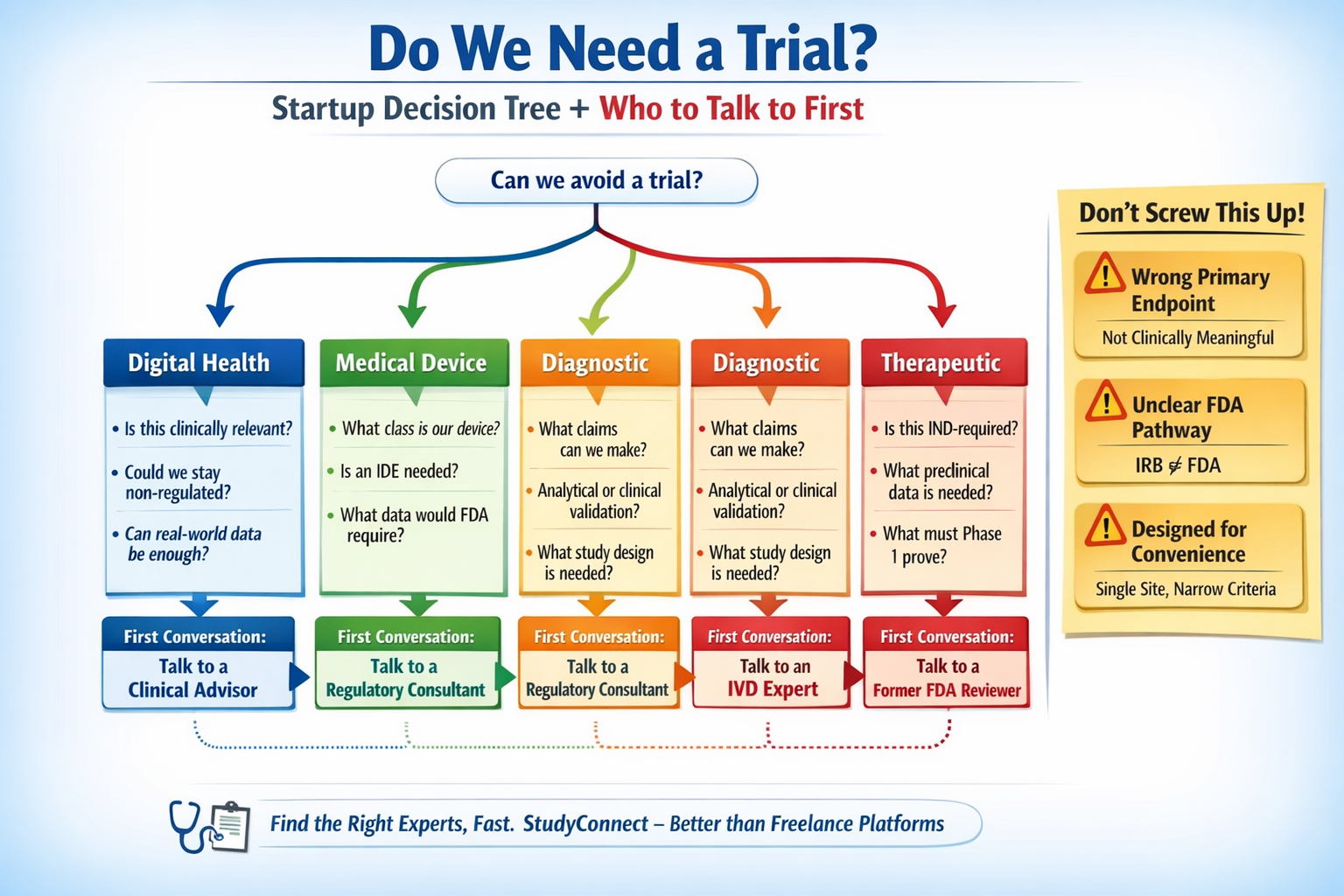

Do we even need a clinical trial?

Most founders can answer this in 10-15 minutes with the right questions. If you are unsure, talk to the right expert before building more.

Decision tree

1) Are you making a regulated medical claim?

Examples: diagnose, treat, prevent, drive clinical decisions

- Yes -> you likely need clinical evidence; confirm FDA pathway early

- No -> you may avoid a clinical trial; consider usability, workflow, RWE

2) Is there meaningful patient risk if it is wrong?

- High risk -> stronger evidence; may require interventional design

- Low risk -> may start with observational evidence and pilots

3) Are you collecting prospective data (going forward)?

- Prospective ->longer set-up; protocol, sites, IRB

- Retrospective -> faster sometimes, but still needs IRB and data access approvals

4) Are you changing care, or observing care?

- Changing care -> likely a clinical trial

- Observing care -> likely an observational clinical study

5) Could real-world evidence (RWE) support your first milestone?

- For some products, RWE or externally controlled evidence can reduce burden

Start here: FDA Real-World Evidence (RWE) Program & Guidance

What to do now

- Write your intended use and claim in one paragraph

- Pressure-test it with a clinician + regulatory expert

- Decide whether you need prospective data or can start with retrospective/RWE

What to delay

- Multi-site expansion

- Fancy endpoints you cannot measure reliably

- Anything that increases scope before pathway clarity

What kind of study applies to you ?

(Digital health / Device / Diagnostic / Therapeutic)

Your product category changes everything.Regulatory pathway, study design, endpoints, and cost all shift.Founders who mix categories usually pay for it later.

Pick your bucket: Digital health, Devices, Diagnostics, Therapeutics

Separate these early.

A "software product" can be digital health or a diagnostic or a device, depending on claims.

1) Digital health (wellness, workflow tools, some CDS)

- Often starts with usability, workflow impact, observational studies

- Biggest risk: accidentally crossing into regulated decision-making claims

2) Medical devices (hardware, wearables, implantables, some software as device)

- Classification drives everything (Class I/II/III in the US)

- Feasibility vs pivotal data expectations differ

- FDA conversations influence endpoints and monitoring

3) Diagnostics (IVD, tests, diagnostic software)

- Claims and intended use define validation needs

- Separate analytical validation vs clinical validation

- Studies fail when claims drift mid-stream

4) Therapeutics (drugs, biologics, cell/gene therapies)

- IND-driven from day one

- Preclinical work and clinical plans are tightly coupled

- Timelines and budgets are the highest

A small misclassification early can force a full redesign later.

Clinical development phase :

Which phase are you really in?

Your "phase" is not just a label.It is a decision about what you are trying to prove and what you can afford to be wrong about.

For therapeutics (classic phases):

- Phase 1: safety, dose, tolerability (often small, controlled)

- Phase 2: early efficacy signal + safety in target population

- Phase 3: confirmatory evidence for approval and labeling

For devices, diagnostics, and digital health (startup reality):

- Feasibility / pilot: does it work in the real workflow? is it measurable?

- Pivotal: does it meet the primary endpoint in the intended population?

- Post-market / real-world: performance in broader populations

Early choices become hard to undo. If your feasibility study collects the wrong data, it often cannot be "upgraded" later.

What success looks like:

Endpoints, Populations, and Claims

Slow down here.Your endpoint and population choices decide whether your results are useful later.

Founder checklist (use this before protocol sign-off):

Primary endpoint (pick one and make it measurable)

- Is it clinically meaningful to a real clinician?

- Can it support your intended claim?

- Can you measure it consistently across sites?

Secondary endpoints

- Only include what you will actually analyze and report

- Avoid "nice-to-have" measures that add burden and slow IRB review

Population (inclusion/exclusion)

- Do you have enough eligible patients at your sites?

- Will the population match your future intended use?

Follow-up time

- Long follow-up can be correct, but it impacts runway

- Short follow-up can make results meaningless

Indication / Intended Use (write it down)

- What is it for?

- Who is it for?

- In what setting?

Geography and sites

- Single-site is easier, but may not generalize

- Multi-site adds contracting complexity and coordination risk

Data capture

- What data comes from EHR vs devices vs manual entry?

- Do you have audit trails, access controls, and a clear data owner?

Three protocol rewrite triggers (watch these closely)

1) Wrong endpoint (not clinically meaningful, not claim-supporting, or needs different follow-up)

2) Unclear FDA pathway (or assuming IRB = FDA)

3) Designing for convenience, not scale (single-site forever, narrow criteria, informal data handling)

Who should you talk to first & the exact Questions to ask

The first conversation should reduce uncertainty, not validate enthusiasm. A networking and expert platform like StudyConnect can help here: it can shorten the time it takes to reach the right clinician, investigator, or

regulatory specialist, instead of guessing.

Digital health

Talk to first: a clinician who would actually use it in practice (plus a regulatory consultant after)

Ask:

- What decision would this realistically influence in your workflow?

- Would you rely on this without human review?

- What would make this unsafe?

- Does this feel like decision support or decision-making?

- Could observational data be enough here?

Medical devices

Talk to first: regulatory consultant with device (IDE) experience

Then: experienced PI, clinical advisor

Ask:

- What class does this likely fall under?

-What similar devices has FDA already cleared?

- Would this require an IDE?

- Is feasibility data reusable for a pivotal study, or not?

- What data would FDA reject even if results are positive?

Diagnostics

Talk to first: diagnostics regulatory expert (IVD experience)

Then: lab director or clinical pathologist, PI

Ask:

- What exact claim could we make with this test?

- Is this screening, diagnosis, or decision support?

- What does FDA expect for analytical vs clinical validation?

- Would retrospective samples be acceptable?

- What would force a complete redesign later?

Therapeutics

Talk to first: regulatory consultant or former reviewer (IND pathway)

Then: PI with indication experience, translational scientist

Ask:

- Is this IND-required?

- What preclinical data must be ready before humans?

- What must Phase 1 prove versus Phase 2?

- What mistakes here would cost us a year later?

- What assumptions should we stress-test now?

The real Clinical Trial Process Map

This is the workflow founders actually live.It is not linear, and coordination is the real bottleneck. Map ownership early and you can save months.

Clinical trial process map: the full journey founders actually live A simple end-to-end map looks like this:

Where complexity spikes:

- Protocol drafts multiply (version control becomes a problem)

- Consent language becomes legal + ethical + technical (especially for data/AI)

- Contracts and security reviews slow site activation

- Recruitment forecasts fail, triggering amendments

Practical tools that help you plan without reinventing documents:

NIH & NIDCR Clinical Research Tools & Template for forms and SOP starting points

NIH Clinical Research Toolboxes for investigator workflows and operational planning

AACT Database to review similar protocols, endpoints, durations, and sample sizes across registered studies

Who conducts clinical trials?

Roles and owners

Clinical trials fail when "everyone helps" but no one owns. As sponsor, your startup owns the outcome even if you outsource execution.

Key roles

- Sponsor : legally responsible for the study

- PI (Principal Investigator): medical leader at the site

- CRO: outsourced operations partner (project management, monitoring, vendors)

- IRB: ethics review board that approves human-subject research

- Regulatory consultant: helps align design to FDA pathway (IND/IDE questions)

- Study coordinator (site): day-to-day participant flow, consent, data entry

Owner per step (simple version)

- Feasibility and claim clarity → Founder + clinical advisor

- Protocol and endpoint lock → Founder/PM + PI + regulatory

- IRB submission and responses → PM/CRO + PI (sponsor accountable)

- Contracts and security reviews → Founder/ops + legal + site

- Data systems and compliance → Sponsor + PM/CRO

- Recruitment plan → Site + sponsor (with real volume checks)

Real startup timeline: Idea to first patient

This timeline is from an early-stage startup I have seen play out. Nothing “went wrong,” but unclear decisions compounded into months.

Company type: Digital health + Clinical decision support

Therapeutic area: Cardiology

Study type: prospective, non-interventional feasibility study

Founder expectation: ~6 months

Actual time: ~11 months

Month 0–1: We should run a clinical study (4–5 weeks)

- Internal debates on population and what success meant

- Hidden cost: no single decision-maker on trial design

Month 2–3: Protocol drafting (6–8 weeks, expected 2–3)

- Protocol went through clinical advisor, external PI, and internal product changes

- Small wording changes shifted endpoints and eligibility

- Unexpected delay #1: Protocol decisions are “sticky” once written

Month 4: IRB selection + submission (about 7–8 weeks total)

- 4 weeks to choose an IRB

- 3–4 weeks for initial review

- Different IRBs asked different AI/data and consent questions

- Unexpected delay #2: IRB questions were mostly about clarity, not ethics

Month 5–6: IRB back-and-forth (about 6 weeks)

- Conditional approval, then requests for clearer criteria and data handling language

- Each “minor” request triggered protocol edits, PI sign-off, resubmission

Month 7: Site onboarding (4–5 weeks)

- Contracting + compliance + data security review

- Unexpected delay #3: sites move on their timelines, not startup timelines

Month 8–9: Recruitment planning (about 4 weeks delay)

- Inclusion criteria too narrow

- Low eligible volume flagged by the site

- Criteria adjustment required an IRB amendment

Month 10–11: First patient in (finally)

- Amendment approval, updated consent, staff retraining

The founders did not lose time because of regulators. They lost time because uncertainty was not resolved early.

Where founders lose months (and why it’s usually avoidable)

Most delays are predictable. Prevent many of them with early expert input and clear ownership.

Common delay points:

- Unclear primary endpoint or too many endpoints

- No single decision-maker on trial design

- Picking the wrong IRB model (central IRB vs site IRB mismatch)

- Consent language gaps (data storage, AI use, access controls)

- Site legal, procurement, and security review surprises

- Narrow inclusion criteria → high screen fail rate → amendment

- Late FDA conversations (IND/IDE surprises)

- Underestimating documentation and training burden

- Ignoring data compliance early (audit trails, role-based access, retention)

This is where StudyConnect fits. Founders waste weeks finding the right clinician, PI, or regulatory specialist through broad marketplaces. A specialized network helps you validate assumptions early, before the protocol becomes expensive to change.

Study start-up checklist

This is the part you can operationalize.Use it as a workflow, not as a one-time checklist.The goal is fewer surprises after you “start.”

A practical workflow from feasibility to site activation:

- Feasibility (Sponsor/Founder + clinical advisor)

- Population availability

- Endpoint measurability

- Workflow fit

- Protocol synopsis (Founder/PM + PI + regulatory input) - 2–3 pages covering claim, endpoint, population, procedures, and data plan

- PI and site shortlist (Founder/PM) - Pick sites that match population and operational capability

- Vendor plan (PM/CRO + sponsor) - EDC, eConsent, labs (if needed), monitoring approach

- Budget and timeline (Sponsor + PM/CRO) - Include buffers for contracting and amendment

- IRB strategy (PM/CRO + PI; sponsor accountable)

- Central IRB vs site IRB

- Submission requirements

- FDA pathway check (Sponsor + regulatory consultant) - IND/IDE or not, and what that implies for design

- Data plan + security (Sponsor + PM/CRO + site IT/security)

- Access controls

- Audit trails

- Retention

- PHI handling

- Contracts (CTA) (Sponsor legal/ops + site) - Negotiate terms, data rights, publication, indemnification

- Site activation (PM/CRO + site coordinator)

- Training

- Documents

- System access

- Go-live checklist

- Training and first patient in (Site + sponsor oversight)- Ensure procedures match the approved protocol

Before you start: The non-negotiable Pre-Trial Checklist

You need these before you spend serious money.

Skipping them is how "small pilots" become large delays.

☐ Confirm trial requirement

☐ Identify PI

☐ Draft protocol

☐ Understand IRB needs

☐ Clarify FDA pathway

☐ Plan data handling

☐ Budget realistically

☐ Endpoint sanity check (clinically meaningful + measurable)

☐ Scalability check (will this design survive multi-site later?)

Templates you can copy:

Feasibility checklist & Site activation tracker

These are simple tools that reduce coordination gaps.They also make CROs and sites easier to manage.

Feasibility checklist (what it should include):

- Target population definition and where patients appear (clinic, inpatient, ED)

- Expected eligible volume per month (per site)

- Primary endpoint definition and measurement method

- Data sources (EHR fields, device data, surveys)

- Operational workflow: who does what at the site

- Risks: high screen fail rate, long follow-up, missing data

- “Stop/go” criteria for moving from feasibility to protocol lock

Use the AACT database to sanity-check norms such as endpoints, sample sizes, and durations.Explore similar trials in the AACT Database.

Site activation tracker (what it should include):

- IRB approval status and versions (protocol, consent, recruitment materials)

- CTA status and key dates (CTA cycle time tracking)

- Site security review status (data flow diagram, access, retention)

- Training completion logs (PI, coordinators, staff)

- System access (EDC/eConsent accounts, permissions)

- Go-live checklist and “first patient in” readiness

The goal is visibility. If you cannot see status, you will not see delays.

Clinical trial testing basics:

Data, Compliance, and Documentation founders forget

Clinical research is documentation-heavy by design.If you treat it like product analytics, you will get blocked later.

Founders often forget:

- Protocol version control (what changed, when, and why)

- Consent versions tied to protocol versions

- Data handling documentation (storage, access, retention, deletion)

- Audit trails (who accessed data and when)

- Role-based access controls

- Training logs and delegation logs at sites

- Adverse event reporting workflows (if applicable)

- Monitoring plans (even for low-risk studies, expectations exist)

Ignoring data compliance early is a common irreversible mistake.It forces retrofits that are slower than doing it right at the start.

FDA and IRB: What founders must understand

You can be IRB-approved and still be misaligned with FDA expectations.

You can also be “not FDA-regulated” and still need IRB approval.

That confusion is costly.

IRB is not FDA: What each one approves

IRB approves ethics and participant protection.

It checks risk, consent clarity, privacy, and whether the study is understandable.

FDA regulates medical products and marketing claims.

It cares whether your evidence supports safety and effectiveness for an intended use.

Common founder confusion:

- “We got IRB approval, so we can use this for FDA later.”

- Not always. The endpoint, population, and data quality may not meet FDA expectations.

- “We are not regulated, so we do not need IRB.”

- If you are doing human subject research with identifiable data, you may still need IRB.

The downstream cost of misalignment is usually a redesign or a new study.

That costs time, morale, and runway.

FDA clinical trial process

This is not legal advice, but it is a practical map.

Validate your pathway early with a regulatory expert.

- IND (Investigational New Drug): usually for drugs and biologics

- FDA expects a clinical development plan tied to preclinical evidence

- IDE (Investigational Device Exemption): for certain device studies

- Device classification and risk drive what is required

- “Not needed” (sometimes): many observational studies and some digital health work

- But claims still matter. If you drift into regulated claims, assumptions break.

A practical way to reduce late surprises is to draft a one-page pathway memo early.

Then pressure-test it with an expert who has done this before.

What decisions are hard to undo later

These decisions create lock-in:

- Primary endpoint (and how it is measured)

- Intended use and claims (what you are trying to prove)

- Population and inclusion/exclusion criteria

- Data capture plan (EHR mapping, audit trails, data ownership)

- Single-site vs multi-site design

- Geography (cross-border data and site rules add complexity)

- Convenience-driven procedures that do not scale

If you are unsure about any of these, slow down and talk to experts.It is cheaper to have a hard conversation now than to amend later.

Budget, vendors, and speed:

How startups keep trials from draining runway

Budgets do not blow up only because of science.They blow up because timelines slip and vendors keep billing.Manage cycle time like a product roadmap.

Budget ranges and what drives cost

Costs vary widely by product type, phase, and geography.Still, you can forecast using public benchmarks and common cost drivers.

What drives cost most (across categories):

- Number of sites (each site adds contracting, training, monitoring)

- Recruitment complexity (screening burden, narrow criteria)

- Data systems (EDC, eConsent, integrations)

- Monitoring approach and frequency

- Protocol amendments (re-approvals, retraining, rework)

- Contracting time (CTA cycle time is a real cost driver)

Where to find credible benchmarks (public sources):

- Protocol patterns and study designs: AACT Database

- Official expectations that reduce rework: FDA Clinical Trials Guidance Documents

- Operational templates that reduce custom legal and ops creation: NIH and NIDCR Clinical Research Tools and Templates

If you want numeric budget ranges, add them with sources or keep the section qualitative.

CRO vs in-house:

When to hire help and what to keep internal

Most delays come from coordination gaps. A CRO can reduce operational burden, but it cannot replace sponsor ownership.

Use more in-house when:

- Single-site, low-risk observational study

- Strong internal PM who can run IRB and site coordination

- Minimal vendor stack

Use a CRO when:

- Multiple sites

- Monitoring requirements are non-trivial

- You need experienced IRB submission support across institutions

- You have limited internal clinical ops experience

What the sponsor should not outsource mentally:

- Claim and endpoint decisions

- Pathway clarity (IND/IDE questions)

- Site selection strategy (do not let it be convenience-only)

- Data handling accountability

StudyConnect’s practical role here is upstream: helping you quickly find clinicians, investigators, and domain experts to reduce uncertainty before you lock the protocol and vendor stack.

CRO selection scorecard & Questions to ask

Picking a CRO is like hiring your trial operating team.

You need a scorecard, not a sales call.

Scorecard categories (rate 1–5):

- Relevant therapeutic area experience

- Experience with your product type (digital, device, diagnostic, therapeutic)

- Startup fit (speed, budget sensitivity, willingness to educate)

- Site network and site relationships (if claimed, verify it)

- Contracting support (CTA cycle time management)

- IRB submission experience for your study type

- Data systems (EDC, eConsent, audit trails)

- Monitoring approach (risk-based vs heavy monitoring)

- Transparency on assumptions (enrollment rate, screen fail rate)

- References from similar-stage companies

Questions to ask:

- What assumptions are you making about enrollment rate and screen fail rate?

- What is your typical CTA cycle time, and what do you do to reduce it?

- Who owns IRB responses and version control?

- How do you prevent protocol amendments?

- Show me a sample timeline with dependencies.

Common red flag

- Promising speed without specifying dependencies

- Vague answers about contracting and site security reviews

- No clear owner for document control

- Overconfidence about recruitment without site volume proof

Speeding up start-up:

KPIs, benchmarks, and where cycle time really gets cut

You cannot speed up what you do not measure.A simple KPI sheet catches delays early, while they are still fixable.

KPI sheet:

- Days to protocol final (from first draft to PI sign-off)

- IRB submission to approval time

- IRB approval to site activation time

- CTA cycle time (sent to fully executed)

- Days to first screened participant

- Screen fail rate (percent screened who fail)

- Enrollment rate (participants per week per site)

- Number of protocol amendments (and reason)

Where cycle time is really cut (without shortcuts):

- Fewer protocol rewrites (get endpoint and pathway clarity early)

- Faster IRB responses (write clearer consent and data language up front)

- Faster contracting (start CTA early, run security review in parallel)

- More realistic recruitment (validate eligible volume, not enthusiasm)

A reality check on recruitment pain comes from practitioners sharing experiences.These discussions are not formal evidence, but they show recurring issues founders underestimate, such as how hard recruitment can be.

See community threads like How hard recruitment can be

What is a Protocol rewrite trigger ?

A protocol rewrite trigger is an early decision that later makes your protocol unusable.It is not a small change. It forces a structural redesign.

In startup life, rewrite triggers show up as “We can fix this later.”Later becomes months, because IRB, PI sign-off, contracts, and training all depend on the locked protocol.

The three triggers I see most often are:

- Wrong primary endpoint locked too early

- It is not clinically meaningful, cannot support claims, or needs different follow-up.

- No clarity on the FDA pathway

- Teams assume IRB approval equals regulatory readiness. Then they discover the study does not align with IND/IDE expectations.

- Designing for convenience, not scalability

- Single-site forever, narrow criteria, and informal data collection that fails when you expand.

If you hear your team debating endpoints weekly, pause and get expert input. That is cheaper than rewriting after IRB and site onboarding.

What is the difference between Analytical validation and Clinical validation ?

Diagnostics are strict because the claim is strict.You must show the test works technically and works clinically for the intended use.

Analytical validation asks: “Does the test measure what it claims to measure?” Think accuracy, precision, limits of detection, interference, repeatability, and robustness.

Clinical validation asks: “Does the test result correlate with the clinical condition or outcome in the intended population?”

This is where study design, reference standards, and representative samples matter.

Founders often mix these up and run the wrong study first.

The result is wasted money and data that cannot support the claim they want later.

If you are building diagnostics, talk early to:

- a diagnostics regulatory expert

- a lab director or clinical pathologist

- an investigator who has validated similar tests

What is Site Activation ?

Site activation is the moment a study site is allowed to start enrolling participants. It is not “the site said yes.” It is “all approvals and operational pieces are in place.”

Before a site is activated, you typically need:

- IRB approval (and the correct, final versions of protocol and consent)

- Executed CTA (contract signed)

- Site security and privacy review completed (especially for digital products)

- Staff training completed and documented

- System access configured (EDC, eConsent, portals) with role-based permissions

- A clear recruitment and screening workflow at the clinic

This is why “first patient in” often slips.Even after IRB approval, sites may still be blocked by contracting or IT/security.

If you track site activation with a checklist and owners, you catch blockers earlyIf you do not, you discover them when you thought you were ready to enroll.

What you should have before you run any clinical research?

You do not need a huge team to start.But you do need basic readiness so you do not burn time in rework.

Minimum prerequisites:

- A written intended use and claim statement (one paragraph)

- A draft protocol synopsis (2–3 pages)

- A named PI candidate (or at least clear site targets)

- A first-pass data flow diagram (what data, where it lives, who accesses it)

- A decision on prospective vs retrospective approach

- A clear owner inside the startup for clinical operations (even if supported by a CRO)

If you lack these, your trial start is likely a false start.

Practical resources -

These are not vendor pitches.

They are public resources that reduce guesswork.

- Use FDA Clinical Trials Guidance Documents to shape protocol choices and reduce later amendments:

- Use FDA Real-World Evidence (RWE) Program & Guidance to explore non-traditional evidence options when appropriate:

- Use NIH & NIDCR Clinical Research Tools & Templates for forms and SOP frameworks:

- Use NIH Clinical Research Toolboxes to plan operational workflows:

- Use AACT Database to analyze similar studies and de-risk endpoint and timeline assumptions:

For founder perspective on participation and recruitment realities, scan discussions like:

- Getting involved in clinical research: https://www.reddit.com/r/clinicalresearch/comments/1feh2dz/getting_involved_in_clinical_research/

- Recruitment difficulty: https://www.reddit.com/r/clinicalresearch/comments/1gkktm0/for_those_whve_been_involved_in_clinical_trials/

Where StudyConnect fits

Most startups do not fail because they cannot execute.They fail because they execute the wrong plan for too long. StudyConnect is designed for the part that most teams underestimate:

Getting to the right clinician, researcher, investigator, or domain expert early enough to prevent lock-in mistakes.

When you use expert conversations well, you can:

- validate clinical relevance before building more

- pressure-test endpoints and populations before the protocol hardens

- spot regulatory boundary issues before you assume “IRB is enough”

- reduce coordination waste by aligning stakeholders early

This does not remove the work.It reduces guesswork so you spend time on the right work.

Get in touch with the team at StudyConnect at matthew@studyconnect.world to help you connect with the right medical advisor.

Final takeaways founders should remember

Clinical trials usually take longer than expected.Most delays come from misunderstandings, not regulators.The most expensive mistakes are the ones that feel small early.

If you do three things well, you avoid many costly delays:

- Lock a clinically meaningful primary endpoint that supports your claim

- Get FDA pathway clarity early (even if you think you are “just doing a pilot”)

- Design for scalability, not convenience, so your data stays usable later